When I was in my fourth and final year of a general arts degree, which I had structured to basically be a less-intense Musicology major, I decided however foolishly that I wanted to pivot for grad school and shift my focus to Performance. I took an extra year between programmes, signing up as a non-degree student to take one extra year of lessons and ensembles through the university, so I could assemble my audition materials and work to earn the money to support myself.

I applied to six schools, auditioning for three in person and three via recording. Of those three, only one school, the University of Victoria, accepted my application. Some time into my first year, the topic of my audition video came up. I still remember my teacher, Lou Ranger, saying: “I couldn’t believe you made it through that recording session. You were such an inefficient player, but you kept going and going by sheer force of will.”

(Incidentally, though this isn’t the topic of this post, I’m immensely grateful for Lou for taking me in to his studio. He saw my video and thought, “I can help him.” One of the other teachers I applied with all but admitted to me that they have so many candidates, the ones who get in don’t even really need to be there to get jobs. Get yourself a teacher who actually wants to teach!)

Through my two years with Lou, there were five topics that made the bulk of every lesson: intonation, soft dynamics, tone colour, transposition, and efficiency. The fifth of those is the topic of today’s discussion: Efficiency, and its flip-side, Endurance.

Endurance

Playing the trumpet, at the end of the day, is metal on flesh. One of those materials is stronger than the other; no matter how incredible of a player you are, the trumpet will always win. My students will be familiar with my Five Golden Rules of the trumpet, and rule number four is: “Trumpet Doesn’t Hurt.” Excessive muscle fatigue, or worse, physical pain, are signs of improper playing technique, and a trumpet player’s goal is to be able to have fun, play easily, and play efficiently. How long should you be able to play in a day? Until people get tired of listening to you.

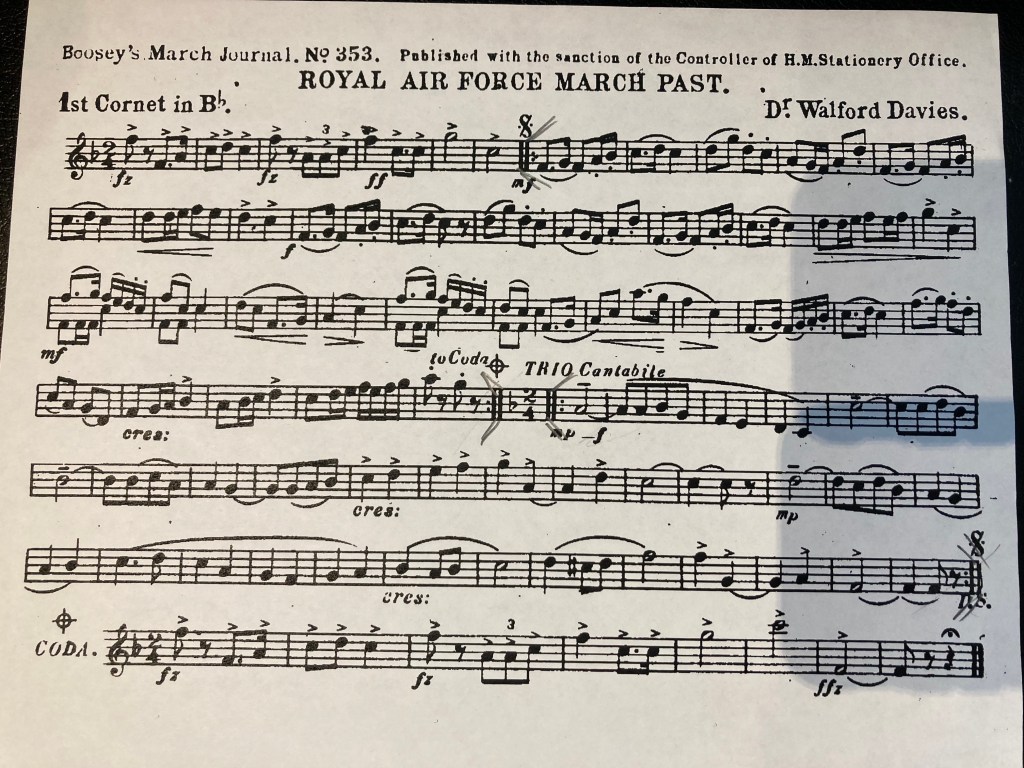

There are two types of endurance: large-scale endurance and small-scale endurance. Large-scale endurance is the ability to play consistently over the course of a whole rehearsal, multiple rehearsals, a whole day, or a whole week of shows. Small-scale endurance is the ability to play continuously from one moment of rest to the next moment of rest. To understand small-scale endurance, think of your average marching chart.

When you work to improve your endurance, the goal is to expand both your ability to play at the small scale and the large scale. To play longer between periods of rest, and to be able to recover (or to not NEED to have to recover as much) between multiple sessions in a day.

An important thing to remember, that any athlete or gym bro will be able to tell you, is that ENDURANCE IS NOT STRENGTH. This goes doubly so for the trumpet: the muscles we’re most concerned about are those of the face, which are universally quite weak compared to other muscles in your body. Check out this diagram here to see what they look like.

Trumpet Muscles

Playing the trumpet, to many a beginner’s surprise, takes much less effort than you would think it does. This is a good thing, because as we just discussed, the muscles of the face are rather weak, and meant for precise and delicate speaking motions, rather than hours of screaming jazz.

To get into the nitty gritty of it, the sound of the trumpet is the sound of fast air vibrating the flesh of the aperture. In order to move the air fast, compression has to be generated in one of four places, which my students hear me talk about all the time: the lips, the tongue, the neck, the lungs. Two of those places are very weak and inefficient, and two of those places are very strong and efficient.

The worst place to compress is with the muscles of the neck. The neck is meant solely to hold your head up, and has no other function in playing the trumpet. Air passes through the trachea from the lungs to the aperture, and the muscles in the neck should have no bearing on trumpet playing.

The muscles surrounding the lips are in many ways the most misunderstood: they NEED to be used, but they need to bear the LEAST amount of the burden that goes into playing. The muscles above and below your lips are effectively not used at all, to keep the centre of your lips relaxed and easy to vibrate. The muscles to the sides of your lips, around your corners, need to be firmly engaged just enough to create a seal, so there’s no air leakage. I tell my students to think of these muscles as reactionary or even involuntary muscles: they REACT to the notes you play, they don’t CAUSE the notes you play. These are the muscles that get fatigued the fastest, and if you feel like they’re giving out, stop playing for a while!

The tongue is a fascinating muscle, or really a bundle of muscles. It’s very flexible, delicate, and boasts incredible endurance for its size. The role of the tongue in playing trumpet, other than the obvious articulation, is actually very similar to the role it plays in whistling: it raises and lowers to add or remove compression from the airstream. Using the tongue to focus the pitch is most obvious when playing the incorrectly-named “lip slurs,” which I exclusively call flexibilities in my teaching.

And finally, the core muscles that surround the diaphragm are by and large the strongest muscles in the system. This is where the wind power comes from, and the core of the First Golden Rule of the trumpet: “AIR WILL GET YOU THERE.” Your core is full of very strong muscles, and so one major key to stave off muscle fatigue is to put most of the work on to the lungs and surrounding muscles, and off of the lips.

Quick Tips

There are a few simple ways to tackle insufficient endurance, so let’s list some basic ones now:

First, make sure you’re not overblowing or playing too loud. Take full breaths in, and use good air support, but play at comfortable dynamics with the right amount of air for the job. You should never feel like you’re shoving air through the mouthpiece with effort, but that you’re letting it out quickly and freely. The airstream is like the jet nozzle on a garden hose, not a fire hose. Likewise, there’s rarely any reason to let your lungs get below 50% full, so keep enough air in the tank that you can blow your way out of any emergency.

Second, stop shoving the damn thing into your face. Relax your left shoulder, to ease tension you might not even realize you had in your left hand. Get your right pinky finger out of the saddle, it’s not an octave key. Again, it’s about metal on flesh, and the metal always wins, so give the flesh a chance. You need enough pressure to create the seal, and no more. This pressure DOES increase as you climb to the higher register, but not nearly as much as young players initially think it does.

Next, make sure you’re taking sufficient rests throughout the day. You’ll accomplish more in three or four 20-minute practice sessions than in one marathon over-an-hour session. This isn’t just good for your physical endurance, but also your mental endurance. We can only concentrate on tasks for so long, so having multiple short sessions can increase your focus as well.

Finally, make sure to vary and balance your practice routine so you aren’t exhausting any one resource faster than the others. Balance high register playing with low register playing, balance loud playing with soft playing, balance articulation exercises with legato and long tone exercises. And of course, balance playing and resting. Even further, balance practicing and rehearsals so that your heavier practice days are lighter on rehearsals, your heavier rehearsal days are lighter on individual practice, and your performance days involve nothing more than a healthy warm-up when possible.

Equipment

I am not a gear-head when it comes to the trumpet, but it is important to have the right tool for the job, especially where the mouthpiece is concerned. I remember having a student come to me for his first lesson, in grade nine band and barely able to play up a C major scale. What was the problem? He bought a used trumpet off of Facebook Marketplace, and it came with a 1-1/2C mouthpiece. He was playing on a mouthpiece far too big for him, with no experience!

As far as mouthpieces go, common knowledge is that smaller mouthpieces are better for endurance and upper register playing, while larger mouthpieces are better for sound quality and middle register playing. For me, I treat your mouthpiece like your shoe size: there’s one size that’s right for you, and it’s what you should play 95+% of the time. Now, that size will change over your playing lifetime, just like your shoe size has changed since you were a kid. But don’t rely on small gear to get a higher sound when your tone quality suffers, try and find a size that strikes a balance and sounds the best for the majority of your work.

This is #notanadvertisement but I’d like to mention my gear for a moment: for about two and a half years now, I’ve been playing on a Wedge 67MDV as my main mouthpiece. It’s the same inner diameter as my previous Bach 1-1/2C that I played before, with a hair more depth inside the cup, but with Wedge’s signature design quirk: the rim is curved concave rather than flat, meaning it fits around your lips rather than lying flat on them. What this does is sit naturally over the corners, instead of pinning them slightly like a traditional flat mouthpiece.

I wouldn’t recommend it to beginners, as you NEED to have a properly-developed embouchure to make a sound AT ALL, unlike a traditional flat rim where the added pressure helps you form the embouchure as a beginner. However, I find that while you’re using the muscles of the face more than the pressure of the mouthpiece, it’s actually BETTER for your endurance, because you’re not pinning the muscles in place with the edges of the rim. Of course, on their website, they advertise high notes, because that’s what people want to hear, but I find my range was pretty much identical to the Bach 1-1/2C, but my accuracy and endurance was much better, and my bright-sound projection improved quickly at the expense of having to re-develop darker tone colours for the first month. It’s worth a try for players with experience, who know what to listen for and are in tune with how their gear feels.

In Conclusion

The one quick tip I didn’t mention above, but will now: the more you can make it a habit to play every day, the better that will be for you. Play smart, play easy, play with wind power, and play efficiently. Lessen up on the arm muscles, keep the lips soft and supple, the corners firm yet flexible, and use the air to power your notes without overblowing. A great exercise to do to ensure you’re not playing with excess tension is to play simple one-octave scales at mezzo-forte up into the high register, starting on G in the staff and ascending chromatically, holding the note on top as a long tone, and then adding some wide vibrato. The vibrato won’t come if the muscles are too tense, so if you can do that without much effort, you’re on the right track to playing easily. Now, take a break, drink some water, and when you get back to practicing, never forget that AIR WILL GET YOU THERE.